Historical Effects of the Transatlantic Slave Trade

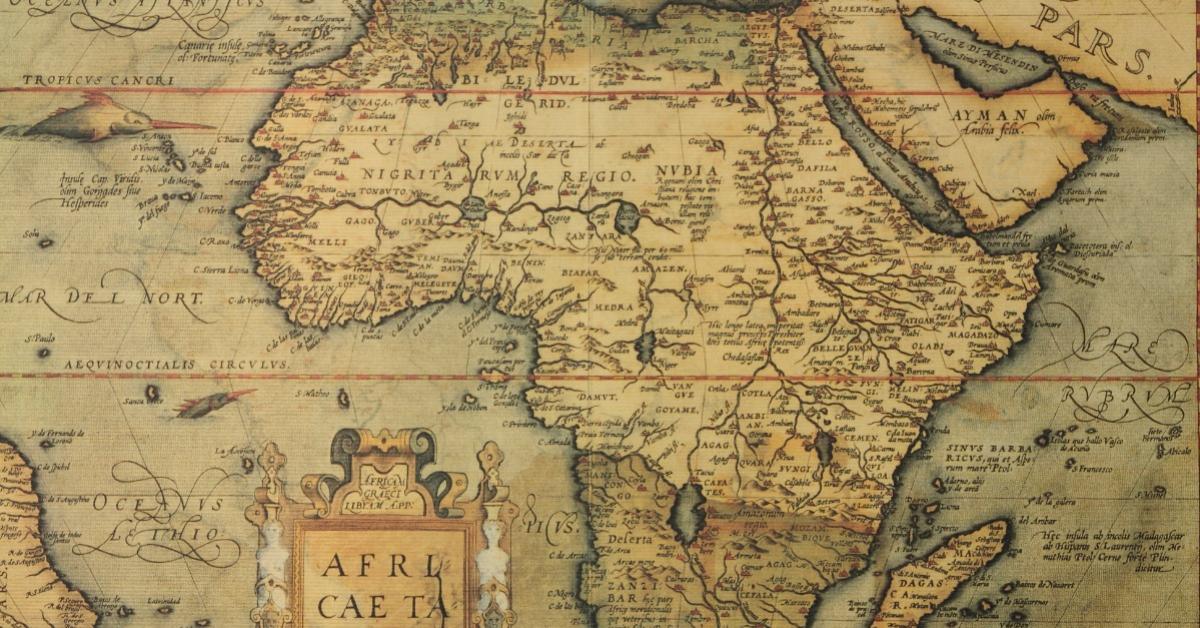

Economists are becoming more appreciative of how historical episodes shape future events. The resurgence of history as an explanatory tool has led economists to publish a series of papers collectively known as the “Deep Roots” literature. These papers cover a wide range of topics, but Africa has been a strong focus due to its unique history of underdevelopment. Some trace Africa’s fortunes and misfortunes to the character of precolonial institutions.

Considering that the transatlantic slave trade occupies a watershed moment in African history, several studies detail its disruptive effects on African societies. Research shows that by prioritizing male exports, the trade led to gender imbalances and high rates of polygyny across Africa. Other research suggests that the transatlantic slave trade increased absolutism in precolonial Africa by 17–35 percent, thereby reducing democracy and liberalism. Prior to the transatlantic slave trade, Africa possessed autocratic institutions, so the slave trade is not the genesis of African autocracy; however, the trade amplified autocratic tendencies.

Debates have also been provoked about the impact of the transatlantic slave trade on Africa’s demography, with many contending that it stalled economic growth by substantially depleting Africa’s labor force. Yet this argument is not without flaws because Joseph C. Miller asserts in a 1982 paper that environmental burdens played a more significant role in restricting population growth and stirring social change in West Central Africa than did the impact of slave exports.

Demographic changes were an obvious outcome of the transatlantic slave trade; however, the trade did not affect all regions of Africa equally. Interestingly, studies on the trade’s demographic impact are becoming infrequent, and more scholars are exploring the trade’s consequences on entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship is a collaborative venture, so it is more likely to scale in high-trust environments, but the slave trade fractured trust and social cohesion in Africa.

The slave trade created incentives for people to betray allies by selling them into slavery. Due to the intensity of the slave trade, people became less trusting of friends and strangers. Testing the association between contemporary developing countries and historical shocks, Ikenna Stanley-Paschal Uzuegbunam and coauthors conclude that social entrepreneurship has been inhibited in places where the slave trade fomented mistrust. Areas that were exposed to the slave trade still suffer from low trust and, as a result, are more likely to struggle in developing community enterprises.

Equally important is a paper by Lamar Pierce and Jason A. Snyder articulating that firms in areas that have suffered great exposure to the slave trade are more likely to exhibit concentrated ownership or be sole proprietors. A possible explanation is that the slave trade weakened institutions and lowered social capital. With lower social capital, entrepreneurs will be demotivated to formalize businesses into limited liability companies. In the long term, this adversely affects one’s ability to raise capital from large and impersonal groups.

Seemingly, the slave trade has negative effects, but did it lead to anything positive? James Fenske, in a review of Africa’s economic history, cites data arguing that the slave trade made affected places more commercial:

Evans and Richardson (1995) note that, after 1700, slaves were captured for export from further and further inland. This necessitated the emergence of new long-distance trading networks, the proliferation of slave caravans, and the development of credit arrangements. This expansion may also have encouraged division between the enslavement and marketing functions, allowing coastal states to become more commercially oriented.

Similarly, according to the 2017 research of Gabriele Cappelli and Joerg Baten, towns that were exposed to the slave trade benefited from European human capital, experienced development, and had a more numerate population. Further, Adeel Malik and Vanessa Bouaroudj posit in a fascinating paper that individuals whose ancestors were historically exposed to the slave trade have higher levels of educational attainment relative to individuals from ethnicities with less exposure to the slave trade. Malik and Bouaroudj note that these effects are primarily driven by coastal countries and, on another note, could imply the transmission of European human capital.

Connecting current developments to past episodes is difficult, and the effects of the past can fade away. However, even when these effects remain, countries are still not enslaved to the past. Indeed, the slave trade resulted in some negative effects for Africans, but it also led to favorable outcomes. Admitting so is simply a statement of fact rather than an endorsement of European imperialism.