Post Content

With so many people obtaining Medicaid coverage in the wake of the Affordable Care Act and during the pandemic, it is worth investigating whether this expanded eligibility is improving health outcomes. Overall, decreases in the proportion of uninsured individuals over the last decade are not being matched by improved life expectancy. Indeed, life expectancy at birth in 2021 was lower than it was when the Affordable Care Act passed. But this fact tells us little about the benefits of Medicaid coverage since the decline has been driven in large part by COVID-19 deaths among elderly patients (often not on Medicaid) as well as increased mortality from accidents and drug overdoses.

To better gauge the benefits of Medicaid, it is necessary to look at more specific health indicators. The federal Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services (CMCS) compiles a large variety of healthcare quality measures that could help us analyze outcomes. Unfortunately, most of these measures are not available for all states and all years, making it difficult to assess performance in a systematic way.

One indicator that is generally available is the rate of low birth weight, which is the percentage of newborns weighing less than 2500 grams, or about five pounds eight ounces. Low birth weight (LBW) babies have “a higher risk of morbidity, stunting in childhood, and long‐term developmental and physical ill health including adult‐onset chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease.” Consequently, reducing the incidence of LBW should improve public health, but Medicaid services are not achieving this outcome.

A 2019 study in JAMA found no correlation between Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion and LBW. The authors used administrative records to obtain rates of LBW (and some other adverse birth outcomes) before and after Medicaid expansion in states that accepted the expansion and those that did not. The change in LBW rates in expansion states was not significantly different than that in non‐expansion states. The authors did find some improvement for Black infants in expansion states, but not for white or Hispanic infants.

Overall, the US is not among the countries that have had the best success in minimizing low birth weight. A 2015 World Health Organization analysis ranked the US 64th among 146countries, with such less affluent nations as Albania. China, and Cuba performing better. Poor US outcomes have been attributed to the use of fertility drugs (which increases the likelihood that a mother will give birth to twins or triplets) and the high rate of Caesarian sections.

According to data from the CDC WONDER Database, 8.3% of US babies born in 2019 were low birth weight. The LBW rate among Medicaid patients was substantially higher, coming in at 9.8% (WONDER also has 2020 and 2021 data, but I chose 2019 data to avoid any pandemic‐related affects).

In the District of Columbia, the LBW disparity between Medicaid‐financed births and those with other types of coverage is especially stark. In 2019. DC’s overall LBW rate was 9.9%. For Medicaid births, it was 12.7% and for non‐Medicaid births it was only 7.4%. And, it does not appear that this disparity is caused by a lack of access to government‐paid medical services: the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) reports that (in 2018) 99.3% of DC Medicaid births took place in a hospital and that 91.7% were attended by a physician, with almost all of the remainder attended by a Certified Nurse Midwife.

The risk of low birth weight can be minimized through proper nutrition, not smoking, and avoiding narcotics. These risks can be controlled with non‐medical interventions. For example, at‐risk mothers can be accommodated at maternity homes, where their diet and substance use can be carefully supervised. The widespread use of maternity homes in Cuba may explain the low rate of LBW in that country (although Cuba’s health statistics have been subject to criticism).

WONDER provides statistics on tobacco use in pregnant women. In DC, the LBW rate among Medicaid tobacco users was 23.7%. Unfortunately, data are not available for other types of substance abuse or malnutrition, however Wallethub recently ranked DC’s drug use fifth among all states (plus DC).

Some states are devoting Medicaid resources to the “social determinants of health”, funding non‐medical services such as housing and nutrition that are intended to address health inequities. DC has an Office of Health Equity that supports “projects, policies and research that will enable every resident to achieve their optimal level of health — regardless of where they live, learn, work, play or age.” But these added efforts are not making a dent in LBW.

Despite spending over $3 billion on Medicaid annually, DC (like other parts of the US), has pregnancy outcomes that are on a par with or even below those of developing countries. It appears that providing costly pregnancy services cannot substitute for the basic health precautions we hope all expectant mothers will take.

Bernie Sanders, in a recent opinion piece, attacked Republicans for trying to get concessions out of the Biden administration under threat of debt default, stating, “Defaulting on our nation’s debt would be a disaster.” Writers at Jacobin echo Bernie’s sentiment.

Unfortunately, it seems like modern socialists are against default; however, historic socialists are not on the same page as our contemporaries. Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, and other socialists were in favor of debt default, and after communist revolutions, the leaders of those regimes almost always defaulted on the national debt, making socialists consistent with libertarians on this issue.

Marx’s rhetoric on public debt ranges from neutral to negative. Despite giving public debt credit for the transition from primitive to modern economies, Marx labels the public debt as “fictitious” and “illusory.” He rightly points out that the money lent was not invested by the state but consumed, and in that sense, it was never capital at all.

In The Communist Manifesto, Marx states, “During the subsequent regimes, the government, placed under parliamentary control—that is, under the direct control of the propertied classes—became . . . a hotbed of huge national debts and crushing taxes.” This casts a negative picture of the national debt. It was an instrument of the propertied classes.

The national debt is clearly placed in the context of class conflict. Marx states,

The accumulation of the capital of the national debt has been revealed to mean merely an increase in a class of state creditors, who have the privilege of a firm claim upon a certain portion of the tax revenue. . . . Titles of ownership to public works, railways, mines, etc., are indeed, as we have also seen, titles to real capital. . . . They merely convey legal claims to a portion of the surplus-value to be produced by it.

The accumulation of surplus value is the defining mark of modern class conflict for socialists, and Marx identifies the public debt as aiding that process.

Friedrich Engels further states, “In order to maintain this public power, contributions from the state citizens are necessary—taxes. With advancing civilization, even taxes are not sufficient; the state draws drafts on the future, contracts loans, state debts.”

The relevance of public debt for Marx and the socialists is intuitive. The “bourgeois state” needs money so it obtains funds from capitalists and imposes a tax on the general populace. The government gets funds, the capitalist class is reimbursed with principal plus interest, and the public is forced to bear the cost. Thus, for Marx, public debt is a machine for exploitation of the proletariat.

If Marx’s criticism of the national debt is not sufficient or clear enough, Lenin starkly attacks it as illegitimate. There are sporadic references to the national debt throughout the collected works of Lenin, becoming more prescient in the writings composed shortly before, during, and after the Bolshevik revolution. In his 1916 “The Peace Programme,” Lenin writes, “As a positive slogan, drawing the masses into the revolutionary struggle and explaining the necessity for revolutionary measures to attain a ‘democratic’ peace, we must advance this slogan: repudiation of debts contracted by states.”

Lenin writes that the “annulment of the national debt” should be a measure of socialist revolution. He makes mention of the “burden of a debt running into billions” and states, “The mountain of war debts shows the extent of the tribute the proletariat and the propertyless masses ‘must’ now pay for decades to the international bourgeoisie.” In 1918, Lenin called again for the “repudiation of the state debt.”

At least the Bolsheviks got something right.

In practice, the socialists defaulted on their debt when taking power as well. Bernie’s precious Soviet Union repudiated their national debts after the Russian Revolution. Lenin’s writings from this time stress heavily the necessity to repudiate the debts contracted by the czar. Repudiation was most definitely a prime goal of Lenin and the Bolsheviks and one of the many motivations for the Russian Revolution.

Furthermore, Communist China repudiated debt accumulated in the form of imperial bonds. Chairman Mao Zedong calls for the repudiation of “all the foreign debts contracted by Chiang Kai-shek during the civil war period” in point 8 of the “Manifesto of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army.”

Revolutionary Cuba did the same. Fidel Castro’s regime refused to recognize the debts accumulated by previous administrations, calling the debt “illegitimate.” As recent as this year, 2023, Cuba was being sued in British court for unpaid Castro-era debt. Should Cuba be obligated to extract funds from their unwilling populace to pay off these debts? Socialists and libertarians alike are opposed to this.

More quotes can doubtlessly be pulled from Marx, Engels, Lenin, Mao, and many other socialists, but Murray Rothbard succinctly and cogently explains the fundamental problem with the national debt:

Shouldn’t public debt be governed by the same principles as private? The answer is no, even though such an answer may shock the sensibilities of most people. The reason is that the two forms of debt-transaction are totally different. If I borrow money from a mortgage bank, I have made a contract to transfer my money to a creditor at a future date; in a deep sense, he is the true owner of the money at that point, and if I don’t pay I am robbing him of his just property. But when government borrows money, it does not pledge its own money; its own resources are not liable. Government commits not its own life, fortune, and sacred honor to repay the debt, but ours. This is a horse, and a transaction, of a very different color.

A socialist should be inclined to agree. Libertarian conflict theory pits the state versus the private sector: “[Government] intervention necessarily creates conflict between those classes of people who are benefited or privileged by the State and those who are burdened by it.” Socialist class theory would accept this, but they broaden it to bourgeois versus proletariat. The libertarian is obliged to oppose the public debt, but the socialist is obliged to oppose all debt, private and public.

Today’s socialists like Bernie Sanders flip this on its head. They oppose private debts, such as student loans, but they defend the sanctity of the public debt. Ironically, the public debt is held by a host of institutions such as the Federal Reserve, mutual funds, banks, state and local governments, pension funds, insurance companies, foreign governments, and governmental agencies. Right now, the American people are paying taxes to transfer wealth to these institutions, many of which progressives and especially socialists would like to see snuffed out.

Bernie wants to pass a progressive income tax and increase corporate taxes to avoid default. He laments about the “top 1 percent” in his recent opinion piece, but the top 1 percent would be devastated by default. Continuing the national debt racket will continue to deepen the issue of inequality that Bernie cares so much about.

Of course, there are consequences of default that would have a negative impact on Bernie’s interest groups, such as the disadvantaged and elderly. For instance, the Social Security Administration (SSA) holds about 9 percent of US debt because, unfortunately, the SSA is required by law to invest its revenue into US debt obligations. Regardless, default will also help Social Security dependents by releasing them from paying US creditors through taxation. The general effects of default may be a net positive for socialists.

Why should any of this stop Bernie though? If he is willing to take the risk of default to avoid Republicans getting the budget they want, he should be in favor of default because of its positive effects. He should at least be cautiously supportive of defaulting on the national debt because the lion’s share of it is held by the rich and powerful. Being against the national debt and pushing for repudiation would make Bernie Sanders more consistent with his predecessors.

So, no, Bernie, defaulting on the national debt would not be a “disaster.” In fact, you should be with the radical Republicans in advocating for default or the total repudiation of US debt as socialists before you have, and if not, then you are merely being an accessory to what Marx called the “class of state creditors.”

Recent articles by Politico and the Wall Street Journal detail the difficult economic environment the Fed must navigate in the coming months along with highlighting the missteps the Fed has made in dealing with post‐Covid inflation. The articles show that in response to inflation, the Fed executed its steepest and fastest series of rate hikes in 40 years. Once again, this has raised several questions into the internal workings of the Fed and the general obscurity with which it has been conducting monetary policy. While the Fed’s recent performance has garnered significant media attention, as my new Cato working paper shows, this failure is only the latest episode in a long‐term trend of discretionary behavior dating back to 2009.

From the mid‐1980s through to the mid‐2000s, Fed policy was generally considered to be good. Academics and Fed officials alike credited good monetary policy with keeping the economy stable during this period (often called the “Great Moderation”). In my working paper, I show that the Fed was much more likely to follow a rules‐based approach during this period as compared to after the financial crisis. In fact, every successive Fed chair since Paul Volcker has deviated further from the rules‐based policymaking that helped the Fed be successful in the first place. Just one fact from the paper: the correlation between the good policy rule of the Fed and their actual policy fell from 75% under Bernanke, to 17% under Yellen, to -2% under Powell.

The primary concern with Fed policy has been that it has kept rates too low. While this has been true since the end of the Great Recession, it has been particularly problematic post‐Covid. In this period, while a standard Taylor rule suggested the Fed should tighten the economy by raising rates, the Fed was easing the economy further by keeping its target rates near zero and then proceeding to buy more assets. Consequently, it was 20 months too late in raising its target rates, by which time inflation had already become entrenched, requiring the sharpest rate hike in 40 years.

Following a monetary policy rule offers several advantages: the Fed’s actions remain clear and concise, it does not require the Fed to precisely gauge the true structure of the underlying U.S. economy, and social welfare has been higher under a rules‐based regime. It is unclear why the Fed has so frequently abandoned the guidance offered by the Taylor rule in the recent past. Particularly concerning is the Fed’s departure from its self‐professed successful policy tools. For instance, a seminal paper by Richard Clarida and his co‐authors showed that good monetary policy kept the economy stable during the Great Moderation. Meanwhile, interest rates departed furthest from the Great Moderation while Richard Clarida himself served as Vice Chair of the Fed. Why did this happen?

Given the benefits of following the Taylor rule, as well as the serious lapses in monetary policy when the Fed acts in an unclear and discretionary manner, perhaps it is time to revisit proposed regulation such as the FORM Act of 2015. This directive would require the Fed to formulate and abide by a rule as a default, but allow it to deviate from that rule provided it explains any departures.

For a detailed analysis, please see my Cato working paper.

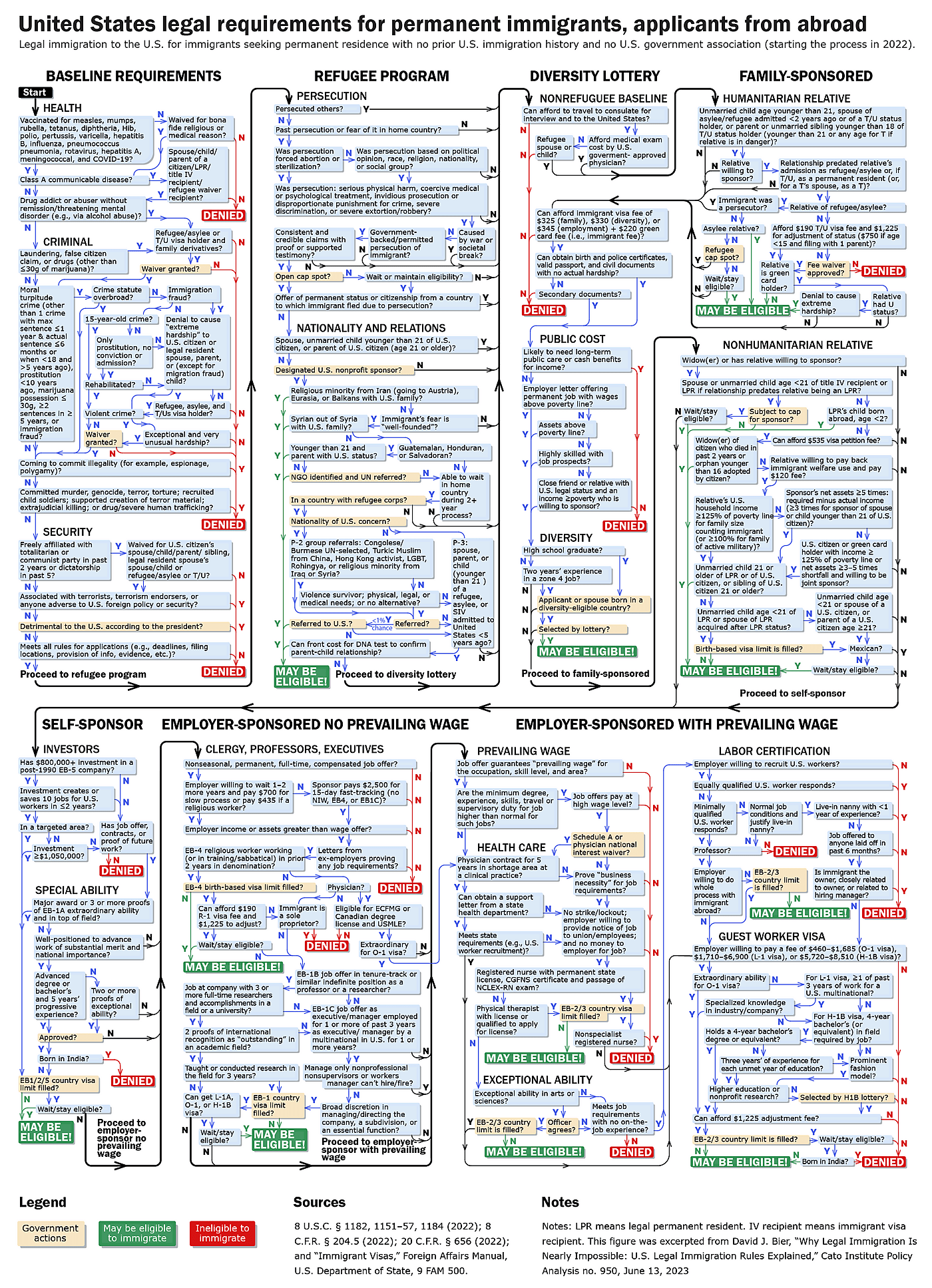

My latest policy analysis published today explains why it is impossible for nearly all immigrants seeking to come permanently to the United States to do so legally. The report is a uniquely comprehensive and jargon-free (to the extent possible) explanation of U.S. legal immigration. Contrary to public perception, immigrants cannot simply wait and get a green card (permanent residence) after a few years. Legal immigration is less like waiting in line and more like winning the lottery: it happens, but it is so rare that it is irrational to expect it in any individual case.

The figure below shows the U.S. legal immigration system for people who are abroad who presently intend to immigrate permanently to the United States. Below I briefly describe the main problems and choke points in this labyrinth.

Guilty Until Proven Innocent

Until the Immigration Act of 1924, everyone in the world was eligible to immigrate to the United States unless the government proved they fell into an ineligible category. In other words, innocent until proven guilty. Since then, the foundational principle of U.S. immigration law is that everyone in the world is ineligible to immigrate unless they prove to the government they fit into an eligible category. The result is that over 99 percent of all those wanting to immigrate to the United States cannot do so legally.

The Narrow Categories

Today, people must show they fit into one of five exceptions to the worldwide ban on immigration: 1) the refugee program, 2) the diversity lottery, 3) family sponsorship, 4) employment-based self-sponsorship, and 5) employer sponsorship. These categories are extraordinarily narrow. Few people can qualify, and thanks to low immigration caps, those who do qualify are often subject to decades-long waiting periods before they can enter legally.

1. The Refugee Program: the Lucky Few

The refugee program is supposed to provide a legal way to immigrate for people who fear return to their home countries. But the rules limit admission to those who fear return based on persecution by a government (or someone the government refuses to control), and only if the persecutor is motivated by someone’s race, religion, political opinion, nationality, or social group. More importantly, the program will only process refugees if they flee from their homes to a group of about 30 countries, and it will only accept applicants from about 30 countries.

Applicants usually need a referral from the United Nations, and they have a less than one percent chance of receiving such a referral. Moreover, the program has a cap, and the government has adopted processing procedures that make filling that cap extremely difficult. Barely one in 5,000 displaced persons will be admitted to the United States under the refugee program. The figure below shows the increasing number of displaced persons and the decreasing number of admissions under the refugee program.

2. The Diversity Lottery: the Golden Tickets

The diversity lottery has four basic rules: 1) applicants must show that they can support themselves at or above the poverty line, 2) applicants must have at least a high school degree or work experience in a job typically requiring a college degree, 3) only people from countries from which fewer than 50,000 people immigrated to the United States in the last five years can apply (excluding a majority of the world’s population), and 4) there are only 55,000 slots awarded through an annual lottery. The chances of winning the lottery and getting a green card have plummeted more than 90 percent since the first lottery was held in 1995.

3. Family Sponsorship: Only the Closest Relatives, Endless Waits

The biggest limitation on family sponsorship is having a qualifying sponsor. The family sponsorship is reserved primarily for the closest relatives: spouses and children of U.S. citizens and legal permanent residents as well as siblings and parents of adult U.S. citizens, and minor children and spouses of those relatives can join except in the case of parents, minor children, and spouses of U.S. citizens. The second limitation is the cap. Only spouses, minor children, and parents of adult U.S. citizens are uncapped, but their numbers reduce the cap of 480,000 for other relatives down to just 226,000. The result is a massive backlog of 8 million cases. For most countries and category combinations, sponsors will die before their relatives can immigrate.

4. Employment-Based Self-Sponsorship: Only for the Most Elite

Employment-based self-sponsorship is available only in the rarest set of circumstances. The three categories are for 1) people with “extraordinary ability,” 2) workers with advanced degrees or exceptional ability who are conducting activities of national importance, and 3) investors able to invest not less than $800,000 and—in some cases—more than $1.05 million in a business that creates 10 new jobs for U.S. workers within 2 years. These highly unusual cases apply to very few potential immigrants, but even in those cases, the government strictly enforces the criteria to make them as difficult to meet as possible. In 2019, for instance, the “extraordinary ability” category had a denial rate of over 40 percent.

5. Employer Sponsorship: Backlogs Wrapped in Red Tape

Employer sponsorship is the one chance where, in theory, it should be open to anyone with an employer sponsor in the United States. In practice, the procedures are so backlogged, so costly, and so time-consuming that very few employers are willing to attempt it except for the highest-paid workers in America. Aside from a few specific occupations, employers must advertise the job to U.S. workers. The process takes years, and even if no U.S. worker applies, very few employers can afford to keep a job open for such a prolonged period.

This is why nearly all employer-sponsored green cards go to people already in the United States who can start working on a temporary work visa, such as the H-1B visa, much sooner while they go through the lengthy green card process. But the H-1B visa is capped at just 85,000. The odds of winning the lottery and ultimately getting an H-1B visa were just 16 percent in 2022. But the even bigger problem for potential immigrants is that the H-1B visa requires a bachelor’s degree, and only 10 percent of the world’s population has a bachelor’s degree.

Even if you have a bachelor’s degree, win the lottery, and convince the employer to pay for the green card processing, the employment-based annual cap is massively oversubscribed. There was a backlog of about 1.4 million in 2020 for a cap of just 140,000. Because every country has the same cap, and immigrants from India account for half of all applicants, the backlog is overwhelmingly Indians who face a lifetime of waiting for a green card.

The U.S. Can Handle Much More Legal Immigration

The U.S. legal immigration system is restrictive in three ways. First, the system is restrictive compared with demand. Nearly 32 million people tried to receive a green card in 2018, while just 1 million were successful, and most could not even try the process. Second, the system is restrictive compared with U.S. history. In the decades prior to the 1920s, the United States routinely permitted a rate of legal immigration three to four times higher than 0.3 percent of the population permitted to receive a green card in recent years.

Finally, the system is restrictive compared with other countries. The United States ranks in the bottom third of wealthy countries for foreign-born share of the population. Even if it accepted 70 million immigrants tomorrow, it would still not surpass the likes of Australia.

Immigration benefits the United States, so there is no reason to place hard caps or strict categorical limits. Moreover, enforcing restrictive laws is costly and results in illegal immigration. The entire legal immigration system is actually designed not to be followed by most people, but to keep most people out. America should return to its system of openness that reflects U.S. traditions and benefits the country.

Joseph Shapiro, UC Berkeley

This article appeared on Substack on June 13, 2023

The state of Oklahoma has recently approved a charter for the St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School, whose curriculum will include religious teaching. Taxpayers will fund the school, so a battle will ensue over whether such funding is desirable or constitutional.

Economic reasoning suggests three possible justifications for government support of education.

First, one person’s education might benefit society more broadly. Economic productivity might be higher, for example, if everyone has mastered “the three Rs.” Some individuals, however, might ignore this “spillover” and therefore choose too little education relative to the social optimum.

Second, people for whom education would be productive (by raising their future income) might underinvest due to myopia, suggesting that even without spillovers, the laissez‐faire level of education might be too low. Some parents, in particular, might choose too little education for their children unless policy makes education cheaper.

Third, people for whom education would be beneficial, with or without externalities, and even without myopia, might have insufficient income to pay for private education and face difficulty in borrowing to finance such an investment (credit constraints).

Reasonable people can debate whether these arguments are convincing. Each has some plausibility, yet each is easily overstated.

In Libertarian Land, governments play no role in education, whether via mandatory schooling, public schools, funding for vouchers or charters, state colleges and universities, or subsidized student loans.

The reason is that, while government support might have the benefits described, this support requires government to define what constitutes education, as the Oklahoma controversy illustrates. Government definition of education limits variety and innovation, and in the extreme facilitates thought control. It is no accident that totalitarian regimes exercise extreme control over their educational systems.

If one nevertheless takes as given that, for the foreseeable future, government will fund education, and have the power to determine what kinds of education receive this support, should taxpayer funding be available for religious schools?

Assuming such education meets the curricular standards that government imposes on all schools, public and private, the answer is yes.

Why? Because religious schools can generate the three benefits that potentially justify government support of education. This is the standard reasoning for allowing private religious schools (or home schooling) to satisfy mandatory schooling laws.

Stated differently, allowing taxpayer funding to religious schools that meet the criteria for funding under the state’s general rules (e.g., teaching the three Rs) is the neutral position for government with respect to religion. This neutrality is the natural interpretation of the Constitution’s establishment clause, which states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

Thus libertarians would prefer little or no government involvement in education. If government does fund education, however, it should not exclude religious schools a priori but instead determine funding based on the criteria that might justify such intervention in the first place.

The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which became effective in 2016, is one of the most detailed legislative schemes in the field of data protection. This article discusses two libertarian-minded objections to its approach. First, I argue that the notion of “right” adopted in the GDPR is flawed. Second, it shows that the GDPR doesn’t protect individuals from data-hungry governments and corporations. In the end, data protection legislation makes people strong in theory but weak in practice, while making powerful private and public entities weak in theory but strong in practice.

A Flawed Notion of “Right”

The GDPR seeks to protect fundamental individual rights relating to the collection and processing of personal data. These include the right to access, the right to rectification, the right to erasure, the right to be forgotten, the right to restriction of processing, the right to data portability, the right to object, and the right to not be subjected to automated decisions.

Libertarian reductionism holds that human rights are natural rights and that natural rights are property rights. The nonaggression principle states that any initiation of violence, that is, any aggression against property, is illegitimate. However, some of the fundamental rights protected by the GDPR violate the nonaggression principle. For example, the right to be forgotten can be invoked by an individual to force tech companies like search engine providers to obscure results about her. The GDPR seems to adopt the view that data subjects own their personal data, but this is debatable.

For example, a user that interacts with Google’s hardware and software, thus producing personal data, is not the only owner of this data because she generated it using Google’s infrastructure. The same goes for any personal data that is produced by interacting with other people, both online and in person. Moreover, when Google shows publicly available information in its search results, it is hardly violating anyone’s property rights.

From a libertarian perspective, it is a big stretch to state that the law should give users the “right” to force companies to delete data about them because this implies that these companies are not free to use their property (their hardware and software) and public information as they wish. Similar objections can be levied against other “rights” as well. The fact that at least some of the “fundamental rights” protected by the GDPR cannot be reduced to property rights is highly problematic: in the absence of well-defined property rights, the GDPR can be used to legalize aggression against persons and entities.

The Practical Ineffectiveness of the GDPR

The GDPR aims at protecting individuals from the exploitation of personal data, but as is often the case with state regulation, it puts individuals at danger and favors big companies and governments.

First, the GDPR understands privacy as a fundamental right, but in most cases, it has to be invoked by individuals in order to be enforced. For example, in the case of the automated processing of data, users are granted the right to ask for human intervention before a decision is taken. Given that the vast majority of people do not have the time, the resources, and the ability to actively engage with the tens or hundreds of private and public entities that handle their data, this amounts to giving controllers and processors carte blanche with regard to data processing in general and automated processing in particular.

Second, the GDPR does little to nothing against the abuse of power that may come from the state. Users’ privacy rights can be suspended or restricted every time there is some kind of public security issue or some kind of legitimate interest. For example, recital nineteen of the GDPR states,

This Regulation should provide for the possibility for Member States under specific conditions to restrict by law certain obligations and rights when such a restriction constitutes a necessary and proportionate measure in a democratic society to safeguard specific important interests including public security and the prevention, investigation, detection or prosecution of criminal offenses or the execution of criminal penalties, including the safeguarding against and the prevention of threats to public security. This is relevant for instance in the framework of anti–money laundering or the activities of forensic laboratories.

These kinds of clauses sound appealing, but they are full of empty words (“democracy,” “important interests,” “public security,” and the like) that are found multiple times in the GDPR. On the one hand, public institutions are supposed to protect individuals’ privacy rights; on the other hand, public institutions can exempt themselves from the obligations laid down in the GDPR because of “national security.” It is a bit ironic that individuals are attributed to so many “rights” that governments and companies are legally authorized to override them in a lot of different ways. Regulators are not protecting data when they make room for exceptions and give themselves and private companies the green light to ignore individuals’ privacy: they’re just making these “exceptions” legal.

Third, the GDPR is very clear in stating that the most important duty of controllers, processors, data protection officers, the European Data Protection Board, and the like is to ensure compliance with the GDPR. However, to comply with the GDPR is one thing, and to protect data effectively is another.

For example, Daniel Solove points out that GDPR consent requirements are fiction because the scale of data processing is so overwhelming that individuals cannot possibly deal with hundreds of privacy notices. Also, individuals are required to take active action in order to invoke their rights, which is something that most people will not and cannot do. Moreover, the GDPR lays down many legal grounds to process personal data that do not require individual consent, like legitimate interest or public safety. In the end, as long as private and public entities comply with the GDPR formally, they do not need to care too much about actual individual preferences and about actual data protection.

The GDPR Paradox

The GDPR both overshoots and undershoots. On the one hand, it overshoots because individuals are granted “rights” that may be used to violate other entities’ property; the main issue is that property rights of personal data are not well-defined. On the other hand, the GDPR undershoots because individual “privacy rights” as defined by European Union regulators are a fiction that can be legally overridden by corporations and by public institutions for a variety of reasons.

The GDPR paradox is that it gives individuals rights that they do not have while undermining their practical ability to protect personal data from powerful third parties. Conversely, private and public processors are denied legitimate property rights but are protected by law in their daily mission to take advantage of personal data. Without a clear definition of property rights and privacy in the domain of personal data, regulations can only generate confusion and paradoxes.