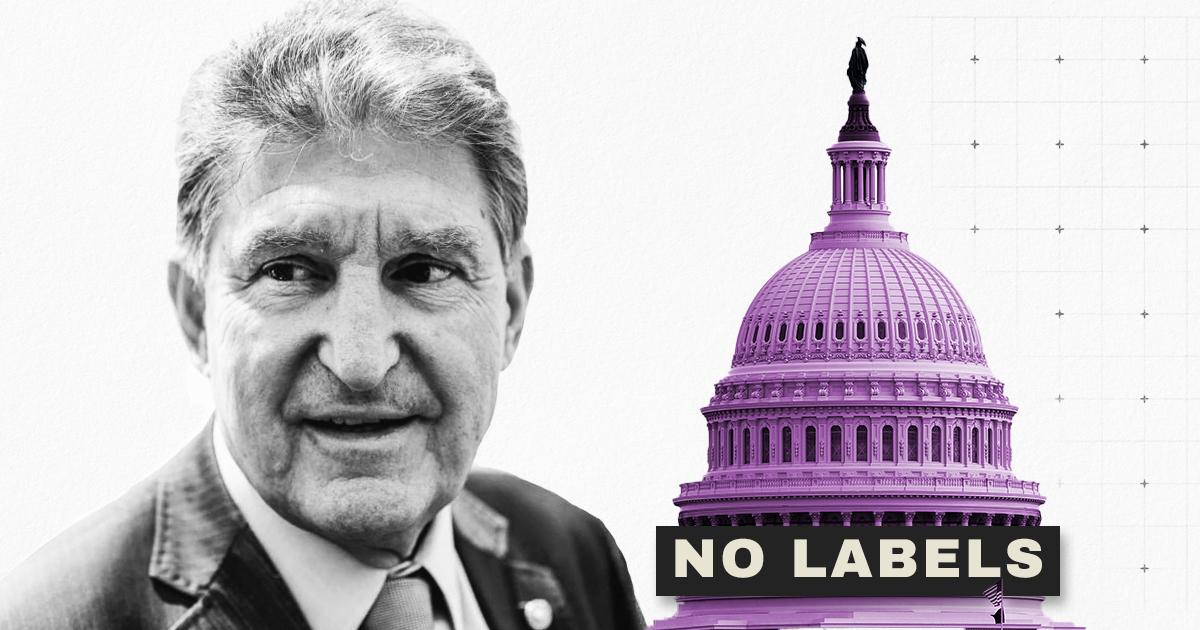

The Problem with Joe Manchin’s Centrism

Last week, Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV) announced he would not seek reelection in 2024. In a Wall Street Journal op-ed, Manchin explained his reasons for leaving. He starts with a relatively noncontroversial assessment of the problems facing America—rising costs, dangerous drugs crossing the border, a large national debt, unsafe communities, and foreign wars that threaten to pull the United States in.

After some platitudes about these not being “Republican or Democratic challenges” but “American challenges,” Manchin concludes:

There are enough votes in Congress to solve or at least make headway against every one of these problems. A genuine commitment to legislating would put America on firmer footing for the next 20 years. But the Democratic and Republican machines have no interest in solutions. Instead, they stoke outrage because doing so brings them fame and funding.

For that reason, Manchin’s done with Congress. He now plans to travel the country to scope out interest in a movement to “mobilize the middle.”

That has many speculating and worrying that the West Virginia senator intends to run as the Democrat on the so-called unity ticket being organized by the centrist group No Labels.

The group has said Manchin’s announcement took them by surprise, but Manchin has a close relationship with No Labels, and his op-ed struck all the same chords as the group’s so-called common sense agenda.

Centrists like Manchin and No Labels can sound reasonable because they often cite the most pressing problems facing Americans and point out that Congress is entirely unable or unwilling to solve them. That’s all true. But things start falling apart when they try to explain how we got here and the way out.

As Manchin sees it, the American people are unified in their values and beliefs but unfortunately Congress has been taken over by two “extremes” that shun the wants and needs of the American people.

In fact, the reverse is true. The more than three hundred million people in the US have many different beliefs, values, priorities, and interests. Politically, there are American socialists, nationalists, libertarians, progressives, conservatives, liberals, monarchists, anarchists, neoconservatives, etc. And then there are the politically disinterested—the largest group by far.

In contrast, Congress is much more unified than the massive population it claims to represent. Ludwig von Mises, who spent many years studying and analyzing comparative systems of political economy, defined interventionism as the prevailing ideology among the world’s governments.

According to Mises, interventionism creates a mixed economy between socialism and capitalism where the bulk of the government’s actions are isolated interventions. Interventionism is built on the idea that the income and wealth of the population “is a fund that can be freely used” for the improvement of society through targeted interventions.

In other words, interventionism is an ideology whose adherents believe, or pretend to believe, that we are perpetually only a handful of government interventions away from fixing most of our problems.

While Mises was focused on economic policy, his analysis applies well to all kinds of government intervention. And so does his insight that, over time, middle-of-the-road interventionism leads to socialism—where the government effectively controls all production.

Mises details how, time and again, government interventions are implemented despite warnings from economists that terrible consequences will result. Then, when those terrible consequences inevitably arise, the government uses them to justify more interventions that themselves have terrible consequences, which are used to justify even more interventions, and so on.

The result is a long march toward tyranny. In his book Crisis and Leviathan, Robert Higgs argues this long march can often be sped up by what he calls the ratchet effect. Some interventions lead to a gradual, continuous decrease in living standards—such as the minimum wage or land-conservation laws. But other interventions, like sending newly created money into credit markets or bombing people in foreign countries, can lead to sudden crises like economic depressions or terrorist attacks.

The fear, uncertainty, and destruction caused by these crises make it much easier for governments to justify previously unthinkable levels of intervention, all in the name of addressing an emergency. But, as Higgs demonstrates, the emergency powers seized by the government are rarely rolled back once the crisis dissipates.

This pattern should be familiar to anyone who’s studied American history. Because the political class is made up almost entirely of interventionists. The political establishment is committed to a specific pace by which the government intervenes more and more in the economy. Meanwhile, the two “extremes” in Congress rarely push for anything more than a slight increase or decrease in the rate at which we travel down this same trajectory.

Understanding this dynamic makes the centrist solutions look a bit absurd. The “big spending” Obama Democrats implemented a top marginal tax rate of 39.6 percent, while the “extreme” Trump Republicans imposed a top marginal rate of 37.0 percent. Are our economic problems solved or at least greatly diminished if a centrist Unity ticket can split the difference and usher in a 38.3 percent rate?

Similarly, the apparently far-right House proposed a $14.3 billion aid package to Israel. The Democrats instead wanted $10.0 billion. Is the key to peace in the Middle East really as simple as “mobilizing the middle” to send $12.1 billion instead?

Centrists like Joe Manchin and his friends at No Labels are right about many of the most pressing problems facing Americans. But they’re wrong to blame extremism and dissent within Congress. The infighting in Washington, while nasty, is largely a sham. The two parties remain unified behind the same destructive ideology—interventionism. If we keep trying the same thing, how can we expect different results?