The Central Bank Policy Interest Rate vs the Natural Rate

According to many commentators, the Fed’s monetary policy, which aims at price stability, is the key factor in attaining stable economic growth. They claim that what prevents the attainment of price stability are fluctuations in the federal funds rate relative to the neutral interest rate, also known as the natural interest rate. Under this view, since the natural interest rate is consistent with stable prices and a balanced economy, Fed policymakers should steer the federal funds rate toward it.

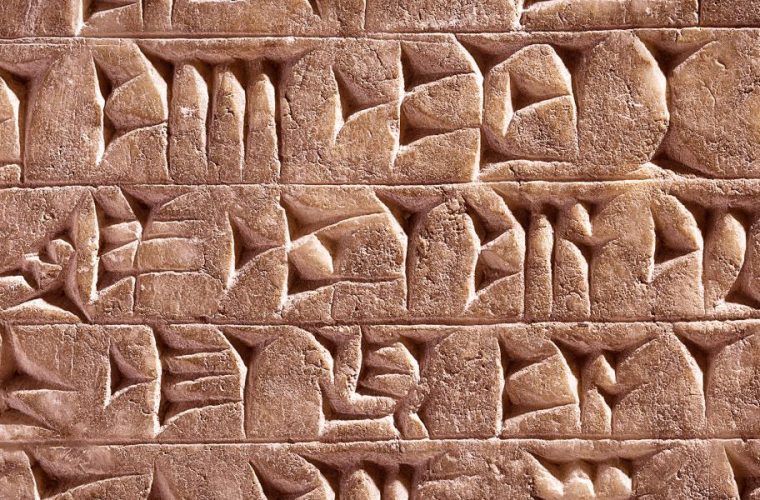

This theory has its origins in the writings of British economist Henry Thornton (1760–1815) and was further articulated by Swedish economist Knut Wicksell in the late nineteenth century.

Knut Wicksell’s Theory of Price Stability

The heart of Wicksell’s theory is the natural interest rate, which he defines as follows:

There is a certain rate of interest on loans which is neutral in respect to commodity prices, and tends neither to raise nor to lower them. This is necessarily the same as the rate of interest which would be determined by supply and demand if no use were made of money and all lending were effected in the form of real capital goods. It comes to much the same thing to describe it as the current value of the natural rate of interest on capital.

Hence, according to Wicksell, the natural interest rate is the rate at which the demand for loans of physical capital coincides with the supply of savings expressed in physical capital.

Wicksell also argues that the natural interest rate is formed by real factors—that is, in nonfinancial markets. If the market interest rate falls below the natural interest rate, then investment will exceed savings, meaning that the quantity of goods demanded will be greater than the quantity supplied. Wicksell assumes that the excess demand is financed by an expansion in bank loans. This leads to the creation of new money, which in turn pushes the general level of prices higher.

Conversely, if the market interest rate rises above the natural interest rate, savings will exceed investment, the quantity of goods supplied will outstrip the quantity demanded, bank loans and the stock of money will contract, and prices will fall.

If, however, the market interest rate corresponds to the natural interest rate, then the economy will be in a state of equilibrium and there will be neither upward nor downward pressures on the price level.

Wicksell maintained that to determine whether monetary policy should be tight or loose, one must compare the two rates. If the market interest rate is above the natural, then the policy should be tight. If it is below, then the policy should be loose. How does one implement this theory? The natural interest rate cannot be observed, so how can one tell whether the market interest rate is above or below it?

Wicksell suggests that policymakers pay attention to changes in the price level. A strengthening growth rate of prices calls for raising the market interest rate, while a weakening growth rate calls for lowering it. This procedure is in fact adopted by all central banks, which use consumer price indexes to measure growth rates.

Real Interest Rate Cannot Be Determined

Would it be possible in Wicksell’s world without money to determine the interest rate for lending present apples in exchange for future potatoes? One could ascertain the quantity of goods exchanged—for example, one apple now for two potatoes in one year. However, since apples and potatoes are not the same goods, there is no way to determine the interest rate that a lender of an apple would receive from a borrower who pays in potatoes.

Only in a world of money can interest rates be determined. Take John the baker, who produces ten loaves of bread and sells them for ten dollars. He then decides to lend the ten dollars in return for eleven dollars in one year because he prefers the latter (a lower time preference). Bob the shoemaker, the borrower, is willing to borrow the present ten dollars and repay eleven dollars in one year because he prefers the former (a higher time preference). Thus, by measuring the values of goods against one another in money and using time preferences to discount future values, the two parties determine a market interest rate of 10 percent.

The natural interest rate could no more be determined without money than the market interest rate could be. But since the natural interest rate, by Wicksell’s definition, must be determined without money, the natural interest rate cannot be determined at all. There is in fact only one interest rate, determined through the interaction of individuals’ time preferences and monetary supply and demand.

We can thus conclude that attempts by economists and central bankers to determine the natural interest rate should be regarded as futile. In a free market without any central banks there would be no need to determine whether the market interest rate is above or below an imaginary natural interest rate.

Conclusion

The ideas of central bank policymakers on this issue emanate from the late nineteenth-century writings of the Swedish economist Knut Wicksell, who thought the key to economic stability was to bring the market interest rate in line with the natural interest rate. Our analysis has shown that it is not possible to determine the natural interest rate. Policies that aim at unknown goals run the risk of promoting more rather than less instability.