Ummm, @PeterGleick, I addressed this 5,958 days ago: Free markets are, in fact, not free

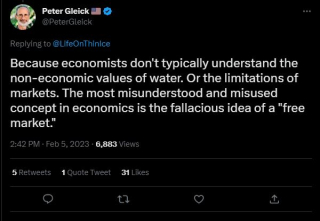

“Dr. Peter Gleick is a leading scientist, innovator, and communicator on global water and climate issues.” He is also a frequent Tweeter and sometimes instigator. Yesterday he tweeted this:

I’m fairly certain Dr. Gleick knows there are a large number of ‘atypical’ economists who understand the non-market values of water (I’m not sure what a non-economic value is because value is inherently economic). Anyway, here’s what I wrote on this exact topic (Are Free Markets Free?) almost 15 years ago…

I’d like to give you two basic definitions of a free market and see which one you agree with:

1) Free market: A market unimpeded by interference from regulation. Buyers and sellers negotiating, in their own interests, to reach an agreement on the price and quanity of a good or service with no intervention by a government or outside agency.

2) Free market: A market in which all costs and benefits of all actions accrue to the participants in the market, and no costs or benefits accrue to anyone outside the market.

Read below the fold for my opinion–the right one of course.

Frequent readers of Env-Econ know that I think #2 is the right definition. That’s not to say that #1 is wrong, it just overstates what most economists mean by a free market. In the following explanation I’m going to oversimplify, just to make my point. I know there an interminable number of caveats you can come up with to counter my argument, but the basic point remains: Free markets are a good thing, as long as they are in fact costless to society.

Let’s begin with my simple definition of a free market: A market in which all costs and benefits of all actions accrue to the participants in the market, and no costs or benefits accrue to anyone outside the market. In order for this definition to hold, all buyers in the market receive the full benefits of their purchase and in the process of consuming their purchase no benefits or costs can be imposed on anyone outside the market–that is, anyone who doesn’t have a choice. Similarly, all sellers in the market must pay for all of their costs of production and no benefits or costs of production can be imposed outside the market.

In an environmental setting, pollution is a classic example. In the process of producing something, say corn, the farmer applies fertilizers to improve the crop yield. Some of the costs and most of the benefits of the fertilizer are borne by the farmer. But, some of the costs of the fertilizer run-off the farm and into nearby waterways. The result? High nutrient loads in nearby waterways resulting in increased algal blooms, lower dissolved oxygen levels, and impure drinking water. To purify the drinking water, nearby towns have to pay extra to remove the extra nutrients. This extra cost has to come from somewhere. In an ideal setting, it would come from the farmer, because the farmer is responsible for generating the cost. But, the free market (as defined in definition #1) creates no incentive for the farmer to account for these costs. If that’s the case, is the free market really free? The additional costs borne by the nearby towns are real costs. They are dollars that could be spent on things the town residents really want, but instead have to be used to ensure their drinking water is clean. The free market is costly in this case.

So how do we solve the problem of costly markets? We create policy/regulation/interventions that ensure that ALL costs and benefits of production and consumption are felt by the buyers and sellers in the market. When that happens, the market will be free to allocate resources efficiently. So in my simple world, there is a role for government in free markets. That role is to make sure that all buyers and sellers in a market have the incentive to choose the right amount of production and consumption.

Notice the emphasis on choice. Buyers and sellers must be free to choose the amount of stuff they want to buy and sell under the constraint that they have to pay all of the costs and receive all of the benefits of those choices. If the market does this on its own (which in many cases it does), then free market #1 and free market #2 are identical and there is no need for regulation. But if the incentives are such that the buyers and seller impose costs or benefits outside the market, then efficiency may require some set of rules set by outside agencies. That doesn’t make the market any less free, just less costly.